Examine the essential ideas, research and context as the work grows through essays, photography and film.

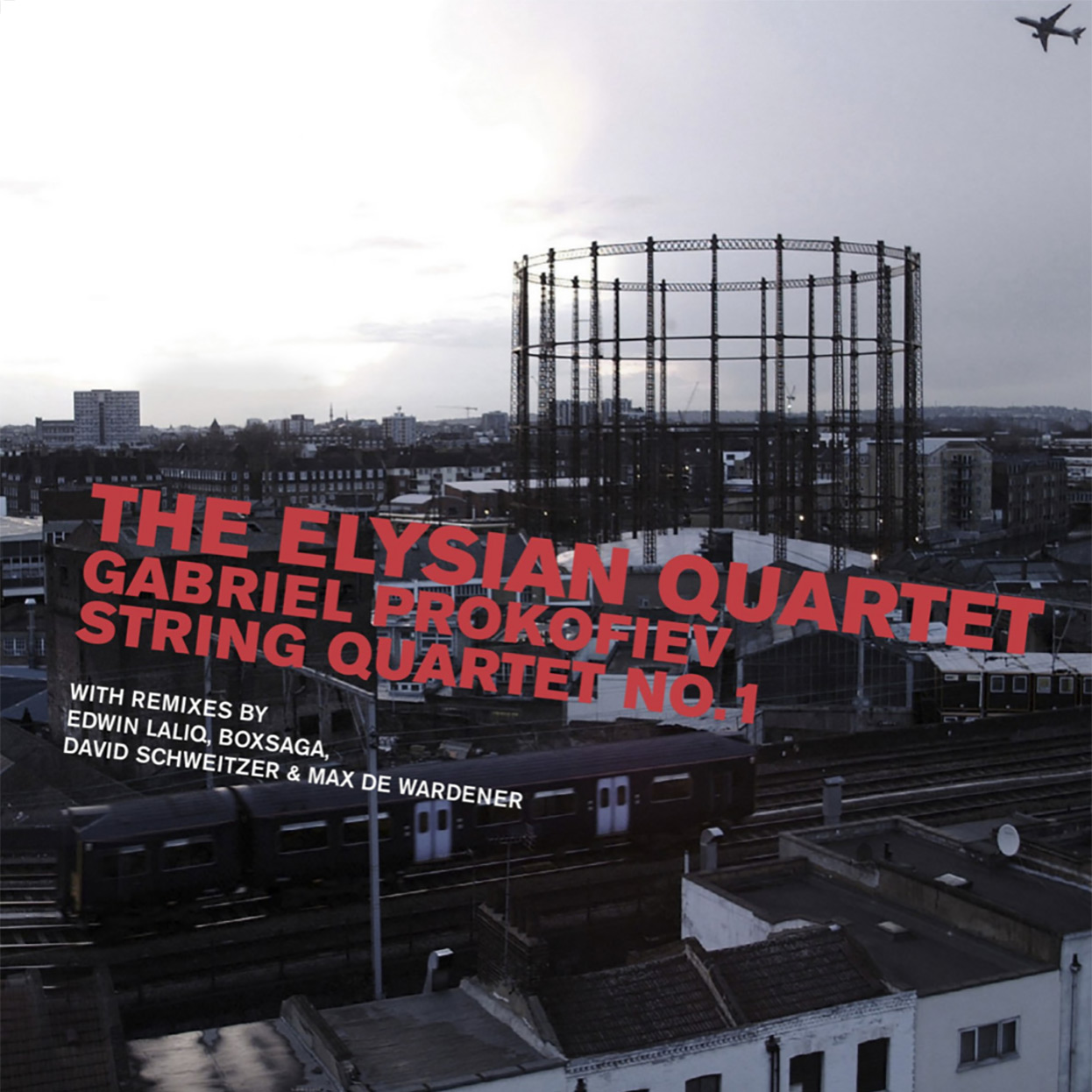

Album artwork for the first release on Nonclassical. Credit: String Quartet No.1 by Gabriel Prokofiev, 2004 © Gabriel Prokofiev

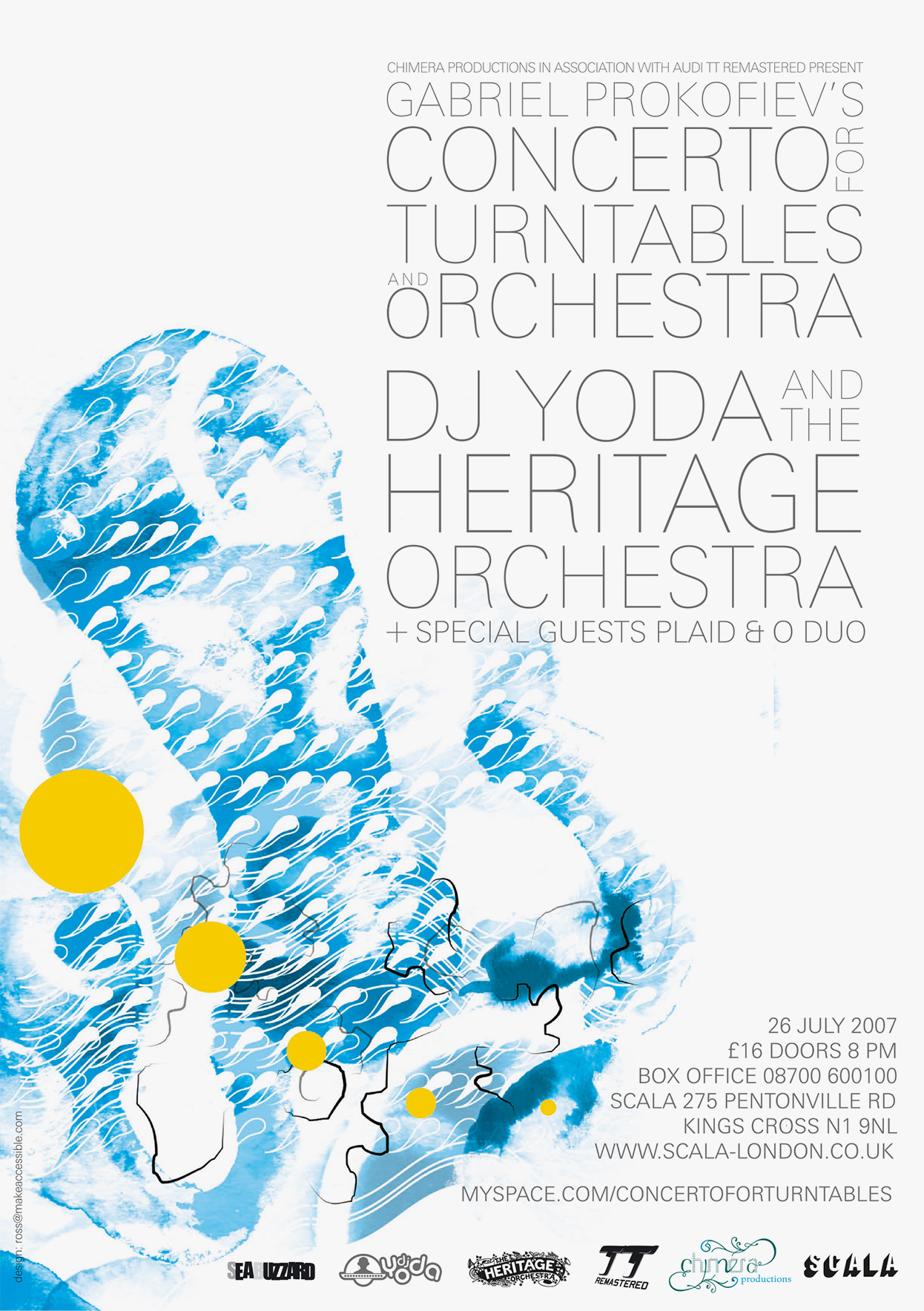

Initial experiments with DJ Yoda, Gabriel Prokofiev and Will Dutta. Credit: Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra by Thomas Brandi, 2006 © Thomas Brandi

About halfway through my PhD at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance, in 2015, I was Researcher in Residence at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, supported by Creativeworks London, AHRC and European Development Fund. One output was a short series of essays (Articles 1 and 2 above) to accompany the ICA’s archival exhibition, Shout Out! Pirate Radio in the 1980s.

Unbeknown to me then, the research I undertook during the 6-month residency would prove formative on my doctoral research, the primary output of which was my second studio album project, bloom. I completed my PhD in 2018 and the curatorial and compositional strategies I developed continue to feed into my work at Studio Will Dutta.

These Covid-days and nights have provided a moment to reflect on that series and to write a new essay where I now fold my own research back into the story I was exploring. This comes ahead of my new experimental broadcast of bloom LIVE/STREAM on 11 November 2020.

Hardcore Continued: Dub’s Instrumental Turn

The non-stop promotion of electronic club music by Gordan Mac and others at Kiss 94.5 FM had a powerful effect on musical language and culture that brings us to the present.

The writer Simon Reynolds talks of a ‘hardcore continuum’ to illustrate the way dub materialises in electronic club music. In the 90s, dub rituals and processes were foundational to jungle, drum and bass, and garage: a new generation of pirate DJs storming the airwaves. Then, in the early 2000s, grime stomped in. As before, pirate radio stations—this time Deja Vu FM, Rinse FM and Heat FM—formed part a tight-knit community of MCs, DJs, house parties, independent record labels, and for the first-time digital channels such as SB.TV. These were the boiler rooms of the early scene.

In his recent survey of grime, Dan Hancox makes the case that the anonymity of pirate radio led to greater sonic diversity in the genre. This suggests a spirited exchange between creative and distributive processes. It is theme we will return to later in the article.

The London-based producer Medasyn worked on some of the breakout successes of grime, including two albums for Lady Sovereign. His idiomatic style is a melting pot of dance music so when he composed his forceful String Quartet No.1, released under his own name, Gabriel Prokofiev, through his own label, Nonclassical in 2004, it felt like a sudden rush of energy into a corner of music languishing under the weight of its own cleverness.

I personally remember this as a seminal moment in the history of a short-lived but intensely active scene in East London. It was not long after that Gabriel and I started to talk about what a non-classical music might be, as we worked together on the Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra.

One of the goals of my doctoral research was to interrogate this idea further because I felt it closely aligned with how I was making bloom. I set out to discover whether non-classical music is a new aesthetic, style or technique. In the following section I share my findings.

A stylistic analysis of non-classical music

The idea of non-classical music is something I inherited from Gabriel Prokofiev. However, I have adapted the use (and spelling) to reference a particular music that has its beginnings on the Nonclassical record label.

There are a limited number of what I would describe as non-classical musical texts. (I have put together a selection on a Spotify playlist here) So the music is far from integrated into music culture, the market and literature and therefore too early to explore as a technique. Is it a new aesthetic? The writer Thom Andrewes suggests ‘the Nonclassical [sic] aesthetic is all about displacement... displacing one style of music into the frame or context of another’. But he does not suggest it requires a new way of listening in the way that Steve Reich did in his description of minimalism as a gradual process.

I argue that non-classical music is a new style where the spotlight is on rhythm and texture (and for the curious reader the analysis that led me to this can be read in full in my PhD commentary. Where it gets particularly inventive (and exciting to listen to) is in the music’s shared characteristics with electronic club music. It is the very fabric of the string quartets, concertos and piano scores that I reviewed.

There is also an essential relationship with the creative and distributive processes as we saw earlier with grime: non-classical music was heard first in the club context (e.g. Prokofiev’s String Quartet No. 1 and Concerto for Turntables and Orchestra first landed at Cargo and Scala in London respectively).

Taking into consideration this brief history, my two previous articles and the music I composed for bloom, leads me to suggest that non-classical music continues the hardcore continuum. It represents a short but energizing new chapter in the history of dub and demonstrates dub’s endless ability to inspire, mutate and regenerate.

Essay by Will Dutta, October 2020. A stylistic analysis of non-classical music is adapted from The Curating Composer, which is available at the libraries of City, University of London and Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance and through the British Library EThOS.

Reference List

Andrewes, T., 2014. We Break Strings: The Alternative Classical Scene in London. London: Hackney Classical Press.

Dutta, W., 2018. The Curating Composer. PhD. City, University of London. Available here.

Hancox, D., 2018. Inner City Pressure: The Story of Grime. London: HarperCollins.

Reich, S., 2002. Writings on Music 1965 – 2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reynolds, S., 1998. Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. London: Picador.

Live shot from world premiere at Scala. Credit: DJ Yoda and Heritage Orchestra by unknown, 2007 © Creative Commons