Examine the essential ideas, research and context as the work grows through essays, photography and film.

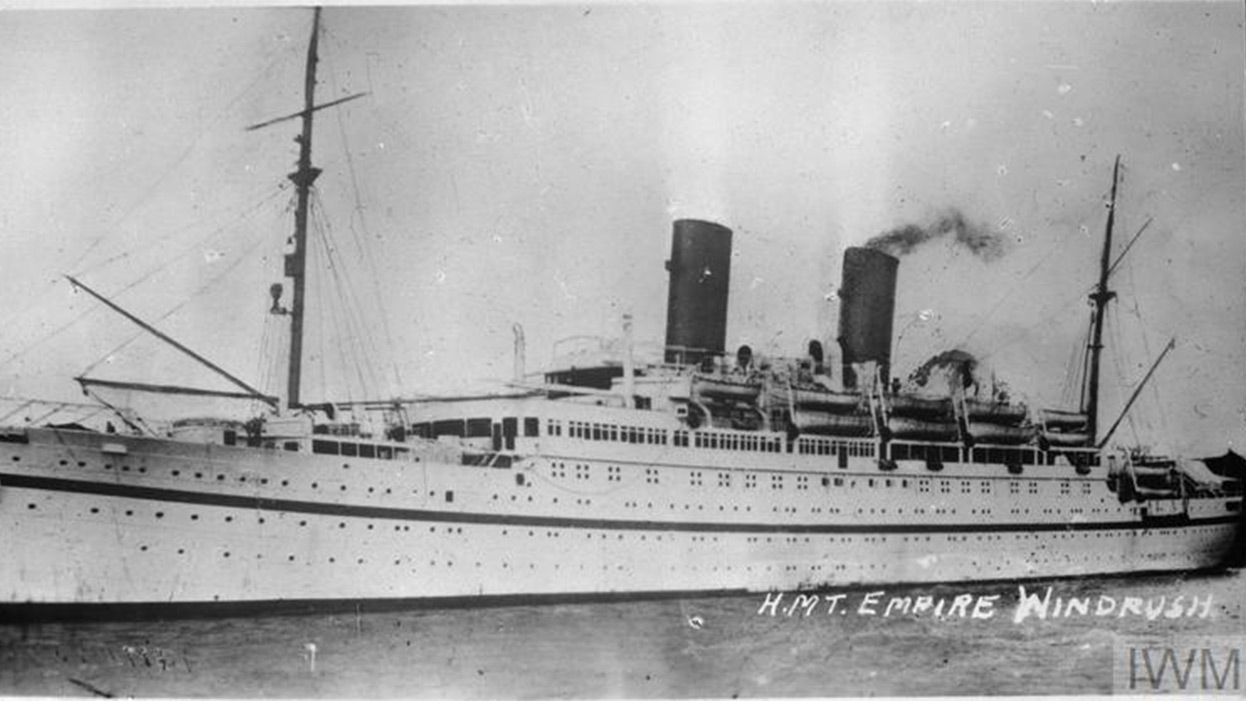

HMT Empire Windrush best remembered today for bringing West Indian migrants to the UK in 1948. Credit: HMT Empire Windrush © IWM (FL 9448)

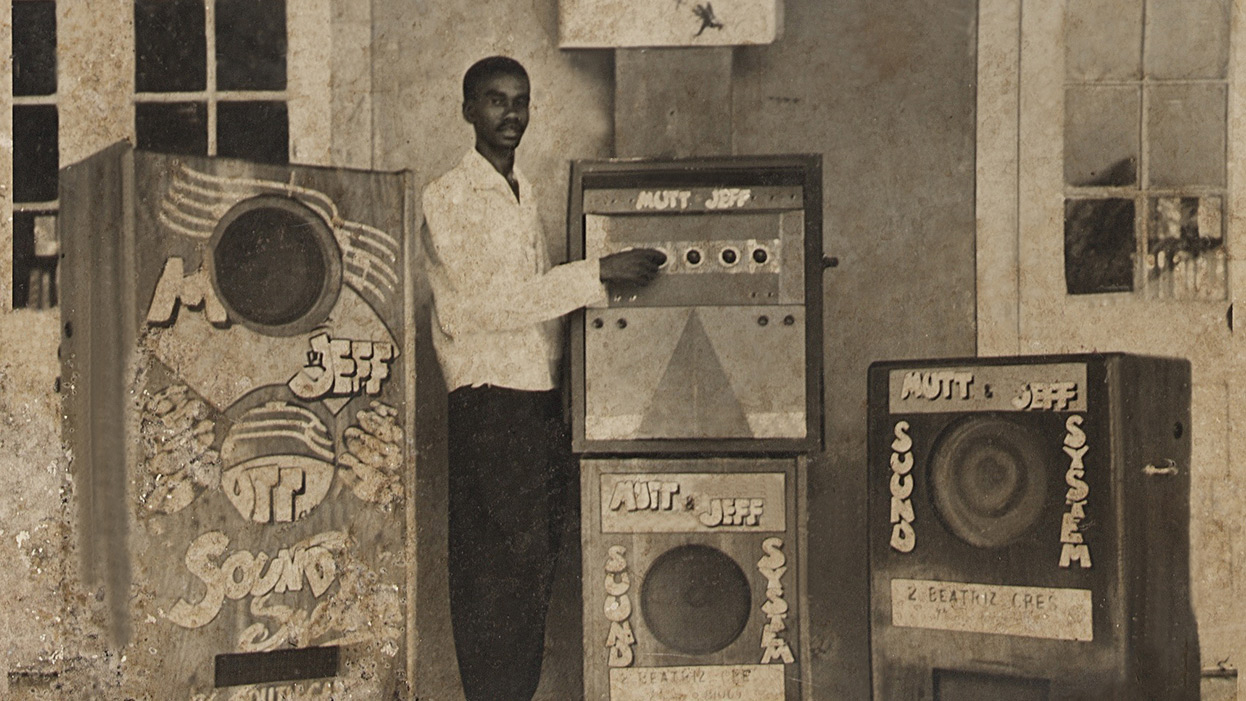

Mutt & Jeff Sound System active in Kingston, JA in the late 1950s. Credit: Mutt & Jeff Sound System by unknown © Creative Commons

is the latest reminder that contemporary music is still bouncing to the rhythms and basslines created and disseminated by the explosion of pirate radio stations in the early 1980s. The canon of electronic club music is littered with producers and DJs who cut their teeth on these illegal broadcasters and MCs whose verbal jockeying has since entered the vernacular. Any story of pirate radio in the 1980s must feature the development of Jamaican sound system culture in the 1940s; the subsequent West Indian migration from the 1950s to 1970s; and the socio-political climate of Thatcherite Britain that left many feeling marginalised and discriminated against.

The sound system, the selector and the deejay: these three integral components of Jamaican sound system culture were first brought to life in Kingston in the 1940s. While radio was the primary means of music dissemination in Jamaica, equipment was expensive and hard to come by. For a few privileged owners, however, it was an opportunity to bring people together and make a little extra money on the side. Listening parties soon gave way to soundmen hiring out their proto-sound systems and services for parties and by the early 1950s two names already stood out as pioneers: Arthur ‘Duke’ Reid and Clement ‘Coxsone’ Dodd. Their musical arms race would prove decisive in driving the scene forward; as technology improved so did the power of their sound systems. These soundmen quickly outgrew playing in homes, yards and halls. For each sound system to operate seamlessly, there were two necessary roles: the selector (‘selecta’), responsible for choosing and playing the records; and the deejay, who spoke (or toasted) between them so to avoid awkward silences as the records were changed. (It is a curious twist that the deejay would later evolve into the MC and the selector the DJ.) One deejay in particular broke the mould when it came to toasting: Count Matchuki who set the style for the patois-rich shout outs and MC-related music coming soon to the UK’s pirate radio stations.

Kingston was also the progenitor of the remix through a musical style that Sullivan (2014) describes as ‘fairly short-lived in Jamaica, peaking in the mid to late 1970s and already winding down in the early 1980s... but whose creative strategies and associated rituals... have continued far beyond its island of origin’: dub music. Moreover, these strategies and rituals would run through the veins of British electronic club music in what Simon Reynolds (1999) described as the ‘hardcore continuum’ in his influential book, Energy Flash. First however, it is necessary to understand how the UK came to be such a hotbed for a variety of electronic club music which would see its wide-spread dissemination via pirate radio.

In the summer of 1948, the Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury, Essex. This marked a boom in migration from the West Indies, which peaked in the 1960s. This major influx of labour was characteristic of the development of post-war Britain and while work was plentiful (British Rail, London Transport and the National Health Service were some of the first employers to provide sponsored recruitment) migrants immediately faced prejudices on arrival, particularly on issues of housing. The first wave of arrivals was briefly put up in a deep level shelter in Clapham South and they quickly found work through a labour exchange on Coldharbour Lane. For this reason Brixton became one of the first West Indian communities in London. Such was the level of discrimination faced by West Indian immigrant families; many had no choice but to move into tiny squalid rooms in Ladbroke Grove, Paddington and North Kensington, much of which owned by the deeply unpleasant and notorious landlord, Peter Rachmann. Work in munitions factories brought immigrants to Merseyside and Lancaster and by the mid-1970s much of Britain’s ethnic minority population lived in London, Birmingham, Leicester, Manchester and Bristol. In spite of the hostilities they faced, these areas became incubators for a new sort of British identity, as Paul Gilroy explains: ‘Britain’s black settler communities... forged a compound culture from disparate sources’. With few organised recreational facilities available to them, those same listening parties and dances, where ‘Jamaicans gathered not only to listen to the trending music of the day, but to discuss community topics, flirt and socialize’, were transplanted wholesale, as Matthew Bennett (2014) puts it, into London’s boroughs.

Essay by Will Dutta originally commissioned by the ICA for their archival exhibition Shout Out! UK Pirate Radio in the 1980s, 26 May – 19 July 2015. Researcher-in-Residence Scheme supported by Creativeworks London, AHRC and European Development Fund.